Jeremy Siegel of Bjarke Ingels Group urges us to seize the initiative and create transformative projects from scratch by harnessing community support.

The coronavirus pandemic is, for many, prompting a re-evaluation of how and where we live and work. From the domestic level to city-wide, and from the regional to the national, built environment issues that were problematic before the pandemic are now all the more acute.

It follows that both commercial clients and the public sector will increasingly require imaginative responses from architects. Practices that are proactive, agile and bold will be well placed to provide the imaginative responses that our fraught present day demands.

At next month’s RIBA Guerrilla Tactics: Reinventing Practice, Jeremy Alain Siegel, an Associate at Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), will be explaining how his practice has employed the tools of design to win over funders, planners, communities and elected city officials alike with daring ideas.

It has done so with a combination of boundless enthusiasm, lateral thinking and appealing communications: bound together in a great proposal that captures the imagination.

What is all the more impressive is that some of its grandest proposals were not responses to tenders or competitions but were entirely self-generated: ideas prompted by a local problem which they took out into the world and made happen.

“We are designers: we understand how different things come together,” Siegel points out. “This allows us to bring a certain amount of useful naivety, in that we can challenge presumptions about what can or cannot be done.”

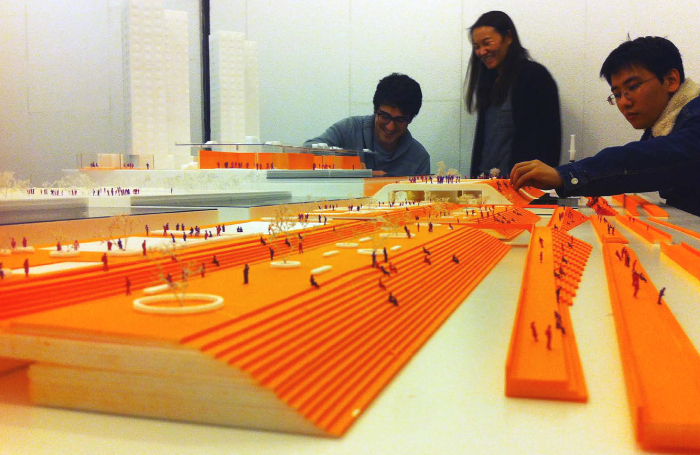

BIG’s most instructive project from this point of view is its reimagining of the iconic Brooklyn Queens Expressway as the half-mile long BQ-Park. The project’s beginnings were entirely self initiated, in a speculative fashion, by BIG’s local Brooklyn office.

The scheme they drew up was so powerful a proposal that it gained momentum within the community and eventually convinced the Mayor to shelve the city’s original remedial scheme in favour of BIG’s vision.

The City of New York was proposing to fix the ageing expressway structure dating from the 1950s, which was corroding and would eventually collapse, by building a temporary highway through the well-loved waterfront park above it.

This was a project very local to BIG’s office. Siegel explains that they were convinced there must be a better solution. They started putting together some pro bono proposals over two or three weeks, then brought in some engineer and landscape friends and the project grew larger and more bold in scope.

“The community group that had formed to fight the plan learned about us,” Siegel recounts. “They set up a meeting to discuss putting together a pro bono proposal: we were able to show them we already had 150 pages of one!”

BIG’s proposal provided a platform for adding significant new parkland, and was eventually accepted by the City as both more feasible and less costly than the original reconstruction plan, while delivering far more benefits to the community. Siegel’s talk of being a “possibilist” and of a designer’s “naivety” is backed up by keen awareness of local politics and community interests.

“You have to make your vision resilient politically by being broad, not just courting narrow interest groups,” he counsels. “Instead you have to identify multiple funding streams, multiple stakeholders and present ideas in ways that they, as stakeholders or funders, can see themselves involved.”

While BQ-Park is, like many of BIG’s projects, a huge infrastructure scheme, there are lessons here for small practices. Siegel says these “guerrilla projects” are carried out by quite small teams. Architects should not underestimate the power of an audacious proposal to generate attention and cut through bureaucracy.

“If you have given a community an appealing idea, they will be advocating for the project when you cannot. They can work for your proposal while you’re elsewhere. That is also why we make videos to articulate a project: a standalone thing that is out in the world, being shared and making an argument for your work.”

Having the good idea is only half of the battle; the rest is communication. Siegel suggests architects might need to invest more thought on written and verbal communication when it comes to design, and not just believe they can “‘draw themselves out of a problem”.

“We always try to explain things in terms people understand. If you want to connect with real people, you should be able to meet anyone and talk to them in a language they can understand.”

The project presentations for BQ-Park and other schemes (viewable on the Bjarke Ingels website) are sterling examples of how to marry text and image, with pertinent leading questions placed in comic book style speech bubbles.

“In presenting a vision, always bring it back to the anchoring point – the catalyst,” Siegel advises. “You don’t want to lose people.”

Tickets are now available for Jeremy Siegel’s talk, The power of a BIG proposal, at the RIBA’s Guerrilla Tactics 2020 online conference.

Learn more insights from other speakers at the conference in our recent features, Is design work moving to the countryside? and Five smart project management boosts.

Thanks to Jeremy Alain Siegel, Associate, BIG.

RIBA Core Curriculum: Business, clients and services.

As part of the flexible RIBA CPD programme, Professional Features count as microlearning. See further information on the updated RIBA CPD Core Curriculum and on fulfilling your CPD requirements as an RIBA Chartered Member.