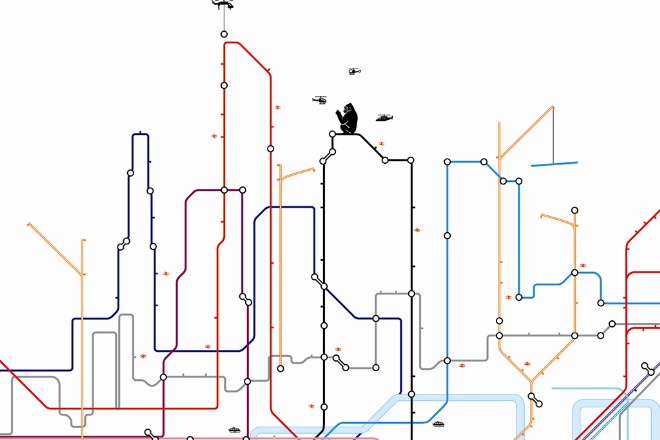

Transport for London’s plans to develop some 75 sites will make it one of the capital’s biggest developers. Here it names the partners for its £3.6bn development framework. Tweeting disgust and frustration about commuting woes could soon become a career-threatening move for the capital’s many construction professionals. The reason is that Transport for London (TfL) is gearing up to become the capital’s most significant development patron. A fortnight ago, the mayor of London’s transport quango unveiled a list of 13 property development companies and consortiums that will be eligible to bid for around 75 development sites across the capital. The baker’s dozen (see list below) of housebuilders, contractors, housing associations and developers have been appointed to TfL’s Property Partnership Framework. The sites, two-thirds of which are located in central Zones 1 and 2, cover 300 acres of TfL land, and are capable of delivering 10,000 new homes and around 10 million ft2 of commercial space, transport bosses claim. The whole initiative is part of TfL’s plan to gear up for the withdrawal of its central government subsidy, currently worth around £700m a year, by generating £3.4bn in non-fares revenue by 2023. So what kind of opportunity does this massive investment from the transport client hold out for the construction industry? What’s TfL building? TfL’s development programme will see the company, hitherto chiefly of interest in construction circles as an engineering client, expand its sway across the capital’s development scene. The sites themselves are a “complete mixed bag”, according to Mathew Evans-Pollard, head of the Deloitte Real Estate team that helped TfL draw up the framework list. Many involve building over existing depots, stations and tracks. Other sites being lined up include bus stations, large roundabouts and redundant operational transport land. They are as diverse as Old Street roundabout and the bus interchange at south London’s Vauxhall station. Some of the sites on the list have been mooted for years, like Victoria coach station, or are the fields of past planning battles, like South Kensington underground station. All have been chosen, though, on the basis that their development can start within the 10 years covered by TfL’s current business plan, explains Evans-Pollard. TfL has submitted planning applications for three so far, the mixed-use development of a former Underground depot at Parsons Green and schemes on top of the new tube stations planned at Northwood and Nine Elms. Each piece of land will be developed as a joint venture. Crucially, instead of selling the sites before a brick has been laid, TfL will take a stake in each development, which will vary between 10% and 90%, but typically just under half. It will then recoup its investment either in the form of a capital receipt when the development is sold or preferably by taking a share of rents generated by leasing out the flats and commercial space that have been built. Design quality This patient approach has been welcomed on the grounds that it should result in higher quality development. TfL and London Underground have a fine track record of architectural patronage, from the iconic tube stations of the 1930s to the Jubilee line extension of the 1990s. However its austerity-era Crossrail stations have received a lukewarm reception. Matthew Carmona, professor of planning and urban design at the University of London’s Bartlett School, says: “If you look across London a lot of development is rather short-termist and not necessarily delivering high-quality places. However, a partnership approach has all of the potential to deliver high-quality places.” David Birkbeck, director of Design for Homes, is even more gushing: “The record to date has been patchy but the possibilities going forward are amazing.” This is because, he explains, companies involved in the JVs won’t have to borrow as much at the outset of the scheme, meaning they are under less pressure to maximise returns by over-developing sites. The JV arrangement also suits the nature of the “over the station” sites that TfL is bringing forward, explains Farrells partner Neil Bennett, who has worked closely on London transport projects dating back to the PwC offices on top of Charing Cross in the late 1980s. “Ownership and maintenance arrangements are going to be so complex that you will never be able to achieve a clean sell,” he says. An example is the problems transport operators often face when negotiating access to maintain track once it is encased in development. In the long term too, TfL will achieve better value for the public purse by delaying its payday, argues Carmona. “This partnership approach is the right way to go because there are opportunities for the public sector to benefit from rising values.” To ensure the bar is raised, Brian Waters, partner at consultant BWCP, argues that TfL should bolster its JV arrangements by appointing a design panel to oversee the briefs coming forward for sites. While masterplans may not be needed for those plots which will only deliver one or two buildings, they will be appropriate on larger sites that have to be knitted into surrounding neighbourhoods. Carmona says: “We need to establish a very clear vision rather than go for the lowest common denominator, ‘stack ‘em high and sell ‘em cheap’ response. Every site will be different and need a very carefully tailored response.” Graeme Craig, director of commercial development at TfL, suggested that masterplans will “sometimes be the right approach”. Whatever comes forward, though, the wave of development that TfL is about to unleash should prove a bonanza for the construction industry. Craig estimates that the projects will create work for “thousands” of engineers, architects and quantity surveyors. Deloitte’s Evans-Pollard agrees: “There are huge opportunities for a whole breadth of organisations to get involved. Each site represents a unique challenge, developing in and around transport hubs in central London, which is where a lot of people want to be.” In particular, there will be “plenty to get the blood flowing” for architects and engineers, he predicts, due to the highly complex nature of many of